Table of Contents

Protein Creatinine Ratio in Clinical Assessments

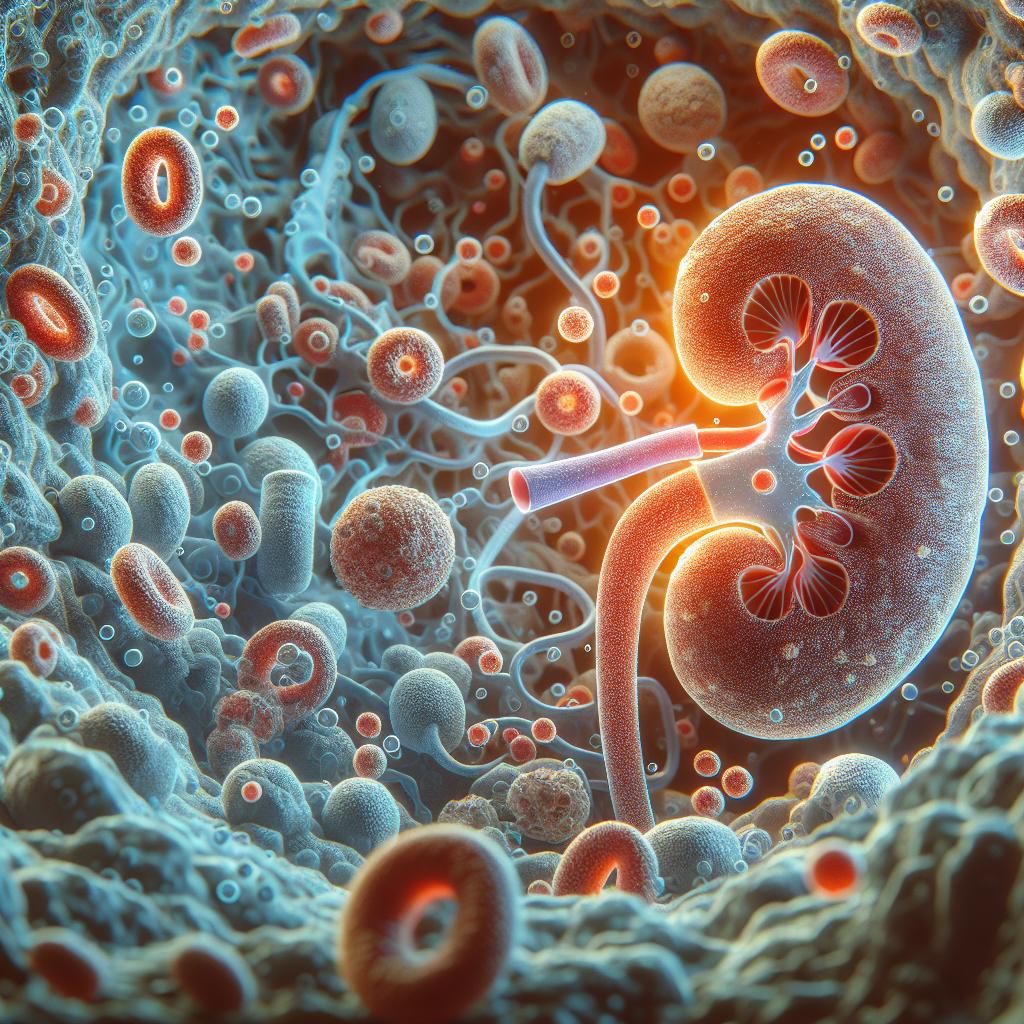

The protein creatinine ratio provides clinicians with a snapshot of kidney function by comparing the amount of protein excreted in the urine relative to the creatinine level. Because urinary creatinine excretion is relatively stable during a given time period, the ratio circumvents the need for a cumbersome 24-hour urine collection. In various clinical contexts—such as early detection of diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive renal damage, and acute kidney injury—the PCR has emerged as an efficient biomarker for quantifying proteinuria. The reliability of this measurement has been enhanced by standardization in laboratory practice and by its ease of collection during a single patient visit. As such, PCR features prominently in clinical algorithms for risk stratification, supporting decisions on aggressive interventions, monitoring treatment efficacy, and guiding follow-up care.

The interpretation of protein creatinine ratio values benefits from careful consideration of diverse factors. Changes in the ratio may reflect underlying alterations in glomerular permeability, tubular function, or a combination of both. For example, in patients with diabetes or hypertension, slight elevations in PCR can signal incipient nephropathy well before overt decline in glomerular filtration rate is evident. In acute settings, a rapid rise in the ratio may indicate a surge in protein loss caused by inflammatory or ischemic injury. In clinical practice, this results in PCR being used as part of an overall assessment to determine whether further diagnostic evaluation, such as renal imaging, biopsy, or additional laboratory testing, is warranted.

The simplicity of the test has helped broaden its use in many epidemiological studies as well as in routine clinical workflows. With increasing evidence linking higher protein creatinine ratios to adverse outcomes, the biomarker is now being integrated into prognostic models that help predict progression of renal disease and cardiovascular events. Such models often incorporate additional factors—like patient age, blood pressure, glomerular filtration rate, and metabolic parameters—to maintain both sensitivity and specificity, as evidenced in contemporary clinical research [1].

Risk Factors Impacting Protein Creatinine Ratio

Multiple risk factors can affect the protein creatinine ratio in patients. The plasma and urinary protein levels may increase due to hemodynamic changes, inflammatory processes, endothelial dysfunction, or direct renal tissue injury. In adults, chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity have been identified as significant contributors to elevated PCR levels. In conditions like diabetic nephropathy, even modest increases in the ratio may have prognostic significance, often serving as an early indicator of glomerular injury.

Additionally, acute pathologies can cause abrupt changes. For instance, ischemia-reperfusion injury—a process that has been studied extensively in other settings such as renal surgery—also has an impact on urinary protein excretion and creatinine clearance. Anesthetic agents; for example, desflurane has been shown to modulate other biomarkers linked with kidney injury such as ITGB1 and CD9, suggesting that pharmacological modulation can influence the overall severity of renal injury and indirectly affect the PCR [6]. Similarly, inflammatory states, whether driven by infectious pathogens or noninfectious conditions like autoimmune diseases, can alter the permeability of the glomerular barrier, leading to transient or persistent proteinuria.

Emerging evidence also suggests that even nonrenal systemic diseases, such as acute heart failure or metabolic syndromes, can induce changes in the urinary biomarker profile. In pediatric populations, for example, research has shown that hospital outcomes related to cardiac function and protein metabolism may be closely linked to the PCR [1]. This underlines the necessity of understanding patient-specific risk factors when interpreting PCR values. The following table outlines several key risk factors and their impact on the protein creatinine ratio:

| Risk Factor | Impact on PCR | Example/Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus | Early elevation owing to glomerular injury | Indicates incipient diabetic nephropathy |

| Hypertension | Increased intraglomerular pressure, protein leak | May correlate with chronic kidney disease progression |

| Acute Ischemia-Reperfusion | Abrupt surge in protein excretion due to inflammation | Seen in surgical settings or acute kidney injury |

| Inflammatory Disorders | Increased permeability from cytokine action | Rheumatic diseases may exhibit transient proteinuria |

| Obesity/Metabolic Syndrome | Altered renal hemodynamics and low-grade inflammation | Contributes to chronic hyperfiltration and proteinuria |

These risk factors need to be comprehensively evaluated by clinicians when using the protein creatinine ratio to guide patient management. In many cases, integrating the PCR with patient history and additional laboratory parameters ensures that subtle changes are not over-interpreted or ignored.

Predictive Models Incorporating Protein Creatinine Ratio

In recent years, prognostic models that incorporate protein creatinine ratio data have become a focal point of nephrology research. These models are designed to predict long-term outcomes related to kidney function, cardiovascular events, and even mortality across different patient populations.

One of the key advantages of using the PCR in predictive models is its ability to capture early and subclinical changes in renal function. For instance, in retrospective cohort studies involving infants with heart failure, a combination of laboratory markers including total protein, pH, and respiratory rate was used to derive a risk score for in-hospital mortality; although this study primarily focused on other biomarkers, the concept can be extended to PCR as a prognostic variable [1]. In adult populations, risk scores that integrate PCR with systemic indicators such as blood pressure, lipid profiles, and kidney function tests have shown promise in predicting the progression of chronic kidney disease and associated cardiovascular morbidity.

Statistical methods such as logistic regression, Lasso regression, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis are commonly employed to evaluate the predictive utility and sensitivity of these models. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is often used as a measure to quantify the model’s accuracy; high AUC values, typically above 0.75, are indicative of robust prediction capabilities. With the improvement in computational techniques and the availability of large datasets, machine learning algorithms have also been incorporated into such models, offering enhanced predictive power by handling high-dimensional data such as proteomic profiles and multi-omics signatures [4].

An example of a predictive model might include the following variables: protein creatinine ratio, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), serum albumin, blood pressure, and demographic indices like age and gender. These models help in stratifying patients into risk categories—low, moderate, and high risk—thus guiding therapeutic decision making. For high-risk groups, aggressive early interventions such as intensified pharmacotherapy or even considerations for renal replacement therapy may be warranted. Moreover, adjusting therapy based on changes in the PCR over time allows for dynamic risk reassessment and personalized patient care.

Examples of Predictive Models in Practice

A recent study constructed a scoring system for in-hospital mortality that combined several independent risk factors. Although the study primarily focused on pediatric heart failure patients, the approach is relevant to chronic kidney disease as well. For instance, such a model might assign points for protein creatinine ratios above a certain threshold and for other laboratory abnormalities, thereby generating an aggregate risk score that correlates with the probability of adverse outcomes [1]. Similar methodologies are currently being explored in large registry studies and randomized controlled trial (RCT) analyses to determine the sensitivity and specificity of these predictive indices.

Furthermore, prognostic modeling in nephrology is increasingly incorporating biomarkers from urinary analysis. Emerging research that investigates genetic markers or transcriptomic profiles, such as those related to inflammatory mediators, may further refine these models. For example, studies have shown that even markers related to lipid metabolism or oxidative stress (like those seen in studies assessing desflurane’s impact on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury) can complement the protein creatinine ratio in predictive frameworks [6]. Consequently, the integration of the PCR with other molecular markers creates a multidimensional approach that holds promise for precision medicine.

Impact of Protein Creatinine Ratio on Treatment Outcomes

The protein creatinine ratio is not only a diagnostic tool—it also plays a key role in monitoring the impact of treatment interventions. In several clinical trials and observational studies, changes in PCR have been linked to changes in therapeutic efficacy. For patients on renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors or sodium-glucose transport protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, for example, reductions in PCR correlate with improved renal survival and lower rates of progression to end-stage kidney disease.

When therapeutic strategies are guided by serial measurements of the protein creatinine ratio, clinicians can dynamically modify treatment plans. For instance, an increasing PCR in a patient with diabetic nephropathy might prompt intensification of blood pressure control or stricter glycemic management. Conversely, stabilization or reduction of the ratio is interpreted as a favorable response, often associated with a decrease in inflammatory stress and lessened proteinuria.

In addition, the protein creatinine ratio has been used in clinical trials as a surrogate endpoint. Its improvement often precedes more definitive long-term outcomes such as reduction in cardiovascular events or the need for dialysis. The prognostic significance of PCR is further enhanced by its correlation with other established biomarkers such as serum albumin, lipid profiles, and even novel markers of inflammation and oxidative stress. Although not every study focuses solely on the PCR, its inclusion in multivariable risk models has provided clinicians with valuable insights into the trajectory of renal disease, thereby enabling proactive therapeutic adjustments [7].

It is also important to factor in patient-specific variables such as ethnicity, baseline kidney function, and comorbid conditions when evaluating treatment outcomes. These factors may influence the baseline protein creatinine ratio and the magnitude of change following therapy. Past research in various disease cohorts has shown that integrating PCR values with patient demographics leads to better-tailored management strategies. This individualized approach, combined with emerging technologies such as machine learning-based predictive models, is paving the way for improved long-term outcomes and optimized resource allocation within healthcare systems.

Future Directions in Protein Creatinine Ratio Research

The integration of the protein creatinine ratio into predictive models represents a promising frontier in personalized medicine and risk stratification for kidney diseases. Looking ahead, several avenues for future research are imperative:

-

Multi-Omics Approaches: As genomic and proteomic technologies evolve, combining PCR with genetic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data may refine risk prediction. Researchers are exploring the integration of urinary biomarkers with circulating molecular profiles to develop a comprehensive predictor of disease progression and therapeutic response.

-

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: With the availability of big data from electronic health records and population-based studies, machine learning models can enhance the predictive accuracy of PCR-based risk assessment. Algorithms that integrate PCR along with other clinical and laboratory variables could potentially predict not only renal outcomes but also adverse cardiovascular events.

-

Longitudinal Studies: Further prospective, longitudinal studies are needed to validate the dynamic nature of the protein creatinine ratio over time. Such studies would contribute to the understanding of how serial changes in PCR correlate with clinical endpoints and improve the timing of interventions.

-

Interventional Trials: Future randomized controlled trials (RCTs) should target interventions that specifically aim to reduce the protein creatinine ratio. Demonstrating that therapies which lower PCR also reduce the risk of hard clinical endpoints, such as progression to dialysis or cardiovascular mortality, would lend additional credence to its use as a surrogate marker.

-

Standardization and Global Collaboration: One of the challenges in incorporating the PCR into routine clinical practice is the variation in measurement techniques across laboratories. International standardization protocols and collaborative research efforts are needed to ensure consistency, enabling reliable comparisons across studies and patient populations.

Continued research will provide deeper mechanistic insights into how changes in the protein creatinine ratio reflect the underlying pathophysiology of kidney diseases. As our understanding evolves, PCR will likely remain an indispensable component of both diagnostic and prognostic models in nephrology and beyond.

Conclusion

In summary, the protein creatinine ratio is a versatile biomarker that plays a critical role in clinical assessments, risk stratification, and monitoring the effectiveness of therapies aimed at preserving kidney function. Although several risk factors—including diabetes, hypertension, inflammatory disorders, and acute injury—can influence its value, the PCR’s simplicity and prognostic relevance have cemented its position in modern clinical practice. The development of robust predictive models that incorporate PCR data, alongside other biochemical and clinical parameters, is already transforming patient care. Ongoing advancements in multi-omics integration, machine learning, and standardization hold promise for further enhancing the utility of the protein creatinine ratio in the years to come.

FAQ

What is the protein creatinine ratio (PCR)?

The protein creatinine ratio is a laboratory measurement used to assess the amount of protein in the urine relative to creatinine. It is an efficient and noninvasive method to detect and quantify proteinuria, aiding in the diagnosis and monitoring of kidney disease.

Why is PCR preferred over 24-hour urine collection?

Because serum creatinine is excreted at a relatively stable rate, PCR offers a reliable estimate of proteinuria from a spot urine sample, eliminating the inconvenience and potential errors associated with 24-hour urine collections.

What are some key risk factors that can affect the PCR?

Chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome can elevate the PCR due to glomerular injury. Acute events like ischemia-reperfusion injury and inflammatory disorders can also lead to significant changes in the ratio.

How is the PCR incorporated into prognostic models?

Researchers integrate PCR with other clinical parameters such as glomerular filtration rate (GFR), blood pressure, and serum proteins to develop predictive models. These models help stratify patients by risk and guide treatment decisions.

What is the future direction of PCR research?

Future research will likely involve multi-omics approaches and machine learning to improve predictive accuracy. Longitudinal studies and interventional trials will further elucidate the role of PCR in predicting clinical outcomes and guiding therapeutic interventions.

References

-

Prediction model and scoring system for in‐hospital mortality risk in infants with heart failure aged 1–36 months: A retrospective case‐control study. (2025). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42110

-

Comparison of serum ischemia modified albumin levels between preeclamptic and healthy pregnant women. (2024). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.61622/rbgo/2024rbgo97

-

C3 glomerulonephritis associated with monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. (2025). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11804883/

-

Circulating levels of miR-20b-5p are associated with survival in cardiogenic shock. (2025). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmccpl.2025.100284

-

Percutaneous vs. surgical revascularization of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with multivessel disease: The SWEDEHEART registry. (2025). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11804248/

-

Desflurane attenuates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulating ITGB1/CD9 and reducing oxidative stress in tubular epithelial cells. (2025). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2025.103490

-

Risk factors for loss to follow-up in patients with gout: A Korean prospective cohort study. (2024). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0318564

-

Aspirin hypersensitivity diagnostic index (AHDI): In vitro test for diagnosing N‐ERD based on urinary 15‐oxo‐ETE and LTE4 excretion. (2025). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11804310/

-

Evidence-Based Anticoagulation Choice for Acute Pulmonary Embolism. (2025). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11805341/

-

Mendelian randomization of blood metabolites suggests circulating glutamine protects against late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. (2025). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11805495/