Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The overuse of antibiotics has led to increased bacterial resistance at both population and clinical levels (Goossens, 2009; Kim et al., 2018). Although large community‐based studies help chart overall trends, case‐based analyses are crucial for connecting exposure types, doses, and durations to the emergence of resistance in vivo (Metlay, 2002). Research utilizing self‐controlled case series (SCCS) frameworks offers unique insights since patients serve as their own controls, thereby reducing confounding factors and permitting analysis of temporal changes in antibiotic resistance following exposure (Petersen et al., 2016; Hallas et al., 2021).

Companion animal studies, for example, have used paired antibiograms from urinary isolates of Escherichia coli to measure changes in resistance patterns after different courses of antibiotic therapy. These insights not only inform veterinary practice but also provide analogies for managing human recurrent Utis. Here, we integrate findings from several recent studies that detail outer membrane challenges, antibiotic synergism, antibiotic step‐down therapy, and clinical stewardship interventions.

2. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Gram‐Negative Bacteria

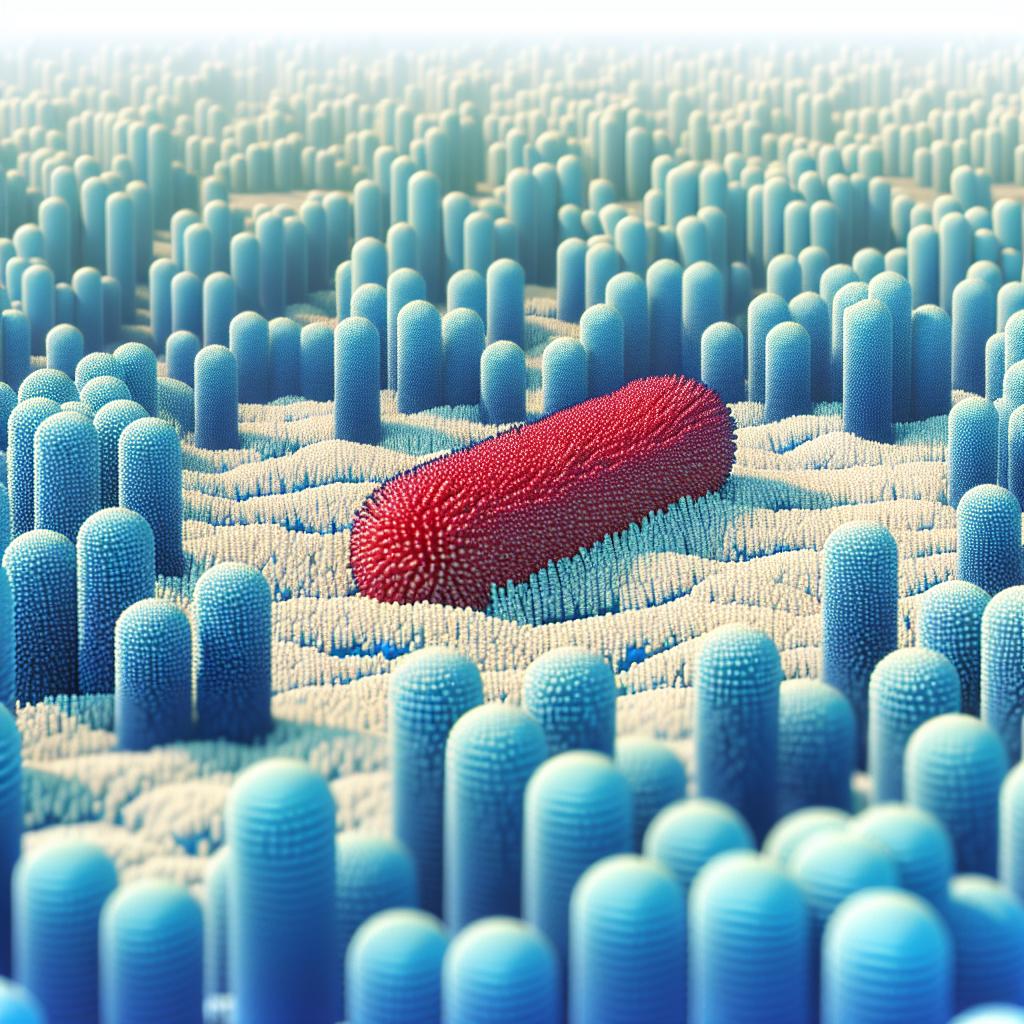

Gram‐negative bacteria are notoriously difficult to treat due to their unique cellular architecture. Their outer membrane (OM) is composed of an asymmetric lipid bilayer with a phospholipid inner leaflet and a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–rich outer leaflet. This LPS barrier, stabilized by divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺), greatly restricts the ingress of lipophilic compounds and many hydrophilic agents. In addition, specific β‐barrel porin channels, although permitting the diffusion of small hydrophilic molecules, also impose size and charge restrictions that limit the passage of many antibiotic classes.

Beyond the OM, efflux pumps—especially the Resistance–Nodulation–Division (RND) family present in Gram‐negatives—serve to expel antibiotics that do penetrate the cell envelope. Such pumps play a fundamental role in both intrinsic and acquired resistance profiles (Choi & Lee, 2019; Amaral et al., 2014). Moreover, Gram‐negative bacteria often produce antibiotic‐degrading enzymes, such as extended‐spectrum beta‐lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases, which further compromise antibiotic efficacy.

Understanding these multifaceted mechanisms is essential for designing new strategies that overcome or bypass these barriers. As demonstrated in recent studies, attention to the physicochemical properties of antibiotics—such as molecular weight, polarity, and rigidity (often termed the “eNTRy rules”)—can facilitate enhanced accumulation inside Gram‐negative organisms (Saxena et al., 2023).

3. Strategies to Enhance Antibiotic Entry and Overcome the Outer Membrane Barrier

Given the formidable OM barrier, researchers have been investigating multiple strategies to improve antibiotic entry into Gram‐negative pathogens. Among these strategies are:

3.1. Outer Membrane Permeabilizers and Synergistic Agents

Permeabilizing agents like polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN) and its derivatives do not necessarily possess direct antibacterial activity; rather, they disrupt LPS cross‐bridging by competing with divalent cations, thereby increasing permeability of the OM. This effect enables otherwise Gram‐positive–selective antibiotics to gain access to intracellular targets—a synergy that has reinvigorated interest in combination therapies (Wesseling & Martin, 2022).

3.2. Optimization of Physicochemical Parameters

Research into the “eNTRy rules” has provided guidelines for optimizing antibiotic structure to enhance penetration. Molecules with a low three-dimensionality, sufficient rigidity, and the presence of an ionizable primary amine are more likely to accumulate within Gram‐negative bacteria. Such modifications can transform Gram‐positive–only agents into candidates that exhibit broader activity (Saxena et al., 2023). These principles are now being applied in the synthesis of novel antibiotic hybrids and prodrugs.

3.3. Siderophore–Antibiotic Conjugates

Another promising approach is the exploitation of bacterial iron uptake systems. Bacteria secrete siderophores—high-affinity iron-chelating molecules—to acquire essential iron. By conjugating antibiotics with siderophore mimetics, researchers have developed Trojan horse–like strategies to import antibacterial agents into bacteria. Cefiderocol, a siderophore cephalosporin, is one such agent that has gained FDA approval for treating hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and complicated urinary tract infections (McCreary et al., 2021).

3.4. Antibiotic Hybrids and Combination Therapies

Hybrid drugs join two or more antibacterial moieties into a single compound, retaining activities of the constituent parts while potentially overcoming multiple resistance barriers. Such hybrids may include a beta-lactam linked to an adjuvant that disrupts the bacterial cell wall, or a fluoroquinolone fused to an aminoglycoside derivative that facilitates OM penetration (Rise of the beta-lactams, 2024). Combination therapies informed by SCCS studies further help in optimizing dosing regimens to prevent both persistence and the emergence of multidrug resistance.

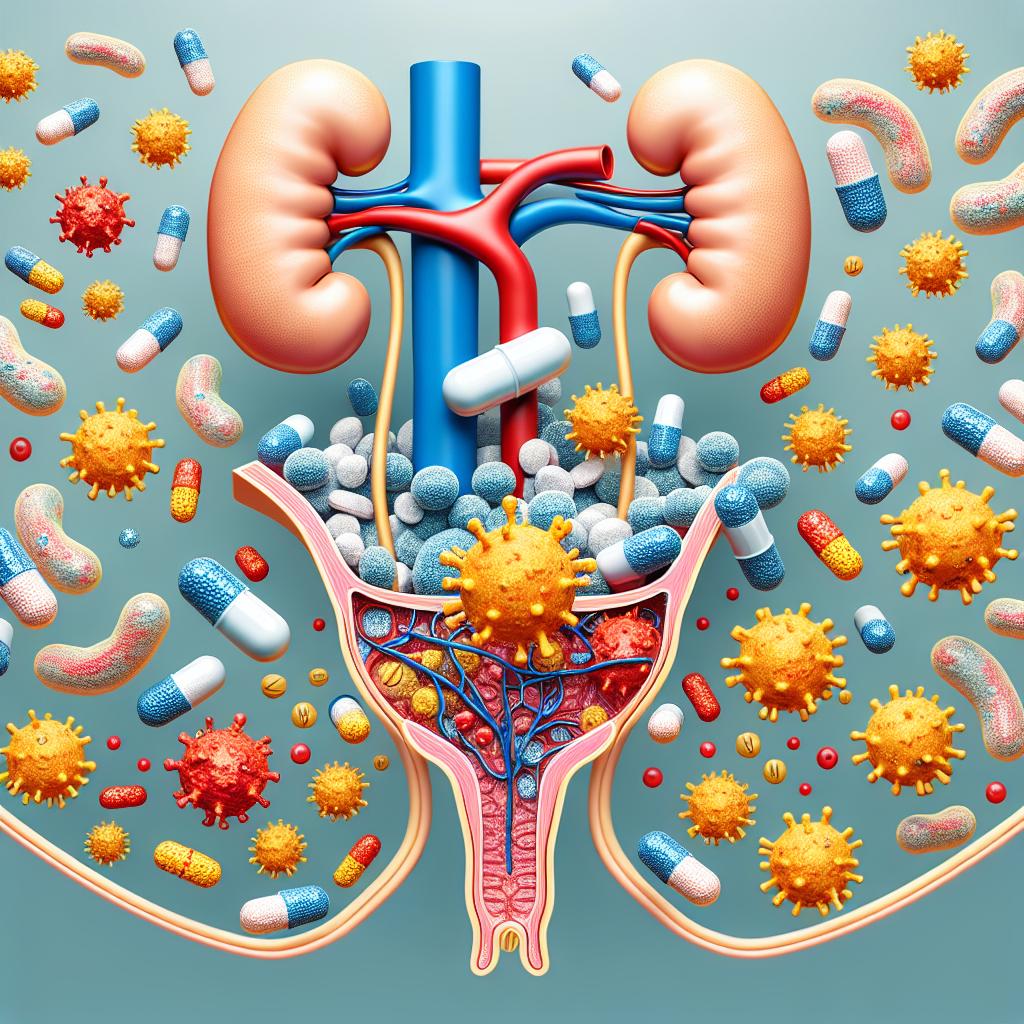

4. Clinical Perspectives on Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) remain one of the most common infections encountered in clinical practice. In particular, postmenopausal women are at increased risk of UTIs due to lower estrogen levels that alter urogenital mucosal immunity and disrupt normal flora (Brennand & Holroyd-Leduc, 2025). Moreover, evidence now supports that recurrent UTIs (rUTIs) are not solely due to reinfection with new strains but often reflect bacterial persistence, where uropathogenic E. coli persists intracellularly within bladder epithelial cells as intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs).

4.1. Role of Intracellular Bacterial Communities (IBCs)

It is now understood that uropathogens form IBCs within the urothelium, which serve as reservoirs for future infections. This has significant clinical implications as many standard antibiotics (e.g., beta-lactams) have poor intracellular penetration, potentially allowing these reservoirs to survive and reinitiate infection (Recurrent UTIs: A Review and Proposal for Clinicians, 2024).

4.2. Pulsed Antibiotic Therapy as a Novel Approach

Given the challenges posed by intracellular persistence, some clinicians propose the use of pulsed antibiotic therapy. This regimen alternates periods of treatment with carefully spaced antibiotic-free intervals to stimulate dormant bacteria into an active metabolic state, where they become susceptible to antibiotic killing. While strategies like continuous low-dose prophylaxis are commonly employed, pulsed courses that leverage intracellular activity (with appropriate agents such as fluoroquinolones or fosfomycin) may prove more effective against rUTIs by targeting both extracellular and intracellular bacteria.

4.3. Antibiotic Stewardship in UTI Management

Finally, antimicrobial stewardship interventions are necessary to reduce the overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and the consequent promotion of resistance. Programs that utilize data-driven performance reports, provider education, and peer benchmarking have shown promise in reducing inappropriate antibiotic use in hospital settings (Antimicrobial stewardship to reduce overtreatment…, 2024).

5. Antibiotic Stewardship and Future Directions

Addressing antibiotic resistance requires coordinated stewardship efforts at both community and hospital levels. Investigations using SCCS designs in veterinary settings have demonstrated that short-course antibiotic treatments can sometimes lead to rapid development of resistance, while longer courses may help maintain susceptibility over time. For example, a study of paired antibiograms in companion animals showed that the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of reversion to resistance was significantly lower with long-course treatment compared to short-course treatment, while multidrug resistance was more common with prolonged exposure in some cases.

Below is a summary table adapted from recent findings:

| Resistance Outcome | Long-Course Treatment | Short-Course Treatment | Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversion to Resistant Phenotype | 0.7 | 8.0 | 0.09 |

| Persistent Resistance | 0.28 | 0.22 | 1.3 |

| Extensive-Drug Resistance | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| Multi-Drug Resistance | 5.3 | 2.0 | 2.65 |

Data adapted from paired-antibiogram studies in companion animals (Examining pharmacoepidemiology…, 2024).

Future research must continue to refine dosing strategies, develop novel compounds based on physicochemical optimization, and evaluate new clinical regimens (such as pulsed therapy) to counter the shifting dynamics of resistance.

6. Data Summary

In recent small animal studies examining urinary isolates of Escherichia coli, researchers utilized a self-controlled study design to compare resistance outcomes in paired antibiograms collected before and after antibiotic therapy. Key metrics included:

- Reversion to Resistance: The number of isolates shifting from a sensitive to a resistant phenotype was markedly lower following long-course treatment (IR ≈ 0.7) compared with short-course treatment (IR ≈ 8.0). The IRR of 0.09 indicates a significantly reduced risk with a longer treatment duration.

- Persistent and Extensive Resistance: While persistent resistance showed a modest increase (IRR ≈ 1.3) in long-course treatments, extensive and multidrug resistance metrics also highlighted the complexity of dosing regimens in managing resistance.

These data underscore the importance of optimizing treatment duration and antibiotic selection to minimize the development and persistence of resistance.

7. Frequently Asked Questions

Why are Gram-negative bacteria more resistant to antibiotics compared to Gram-positive bacteria?

Gram-negative bacteria possess an outer membrane that is rich in lipopolysaccharides, forming a robust barrier that reduces permeability. In addition, they have efficient efflux pumps and produce enzymes (such as beta-lactamases) that degrade antibiotics, which together contribute to higher resistance levels.

What are the “eNTRy rules” and how do they assist in antibiotic design?

The “eNTRy rules” refer to guidelines for enhancing the accumulation of antibiotics in Gram-negative bacteriThey suggest that molecules with a low three-dimensionality, high rigidity, and an ionizable primary amine are more likely to penetrate and accumulate inside these bacteria, thereby improving antibiotic efficacy.

How might pulsed antibiotic therapy improve treatment outcomes in recurrent UTIs?

Pulsed antibiotic therapy involves cyclical treatment periods interspersed with antibiotic-free intervals. This approach aims to force dormant intracellular bacteria out of their quiescent state, rendering them metabolically active and more susceptible to antibiotic killing, thus potentially reducing recurrence rates.

What are siderophore-antibiotic conjugates and why are they important?

Siderophore-antibiotic conjugates couple an antibiotic with a molecule that mimics bacterial siderophores—compounds used by bacteria to capture iron. This “Trojan horse” strategy exploits the bacteria’s iron uptake system to increase antibiotic entry into the cell. Cefiderocol is a prime example, having been approved for treating severe infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens.

What role does antimicrobial stewardship play in managing UTIs?

Antimicrobial stewardship programs aim to optimize antibiotic use, reduce unnecessary exposure (especially in treating asymptomatic bacteriuria), and limit the development of resistance. These programs involve education, performance reporting, and data-driven guidelines to ensure appropriate therapy for UTIs and other infections.

8. Conclusion

Overcoming antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria requires a multifaceted approach that integrates advances in molecular design, clinical therapy optimization, and robust stewardship practices. By understanding the intricate mechanisms of resistance—from the protective outer membrane to efflux pumps and enzymatic degradation—and applying strategies such as outer membrane permeabilizers, siderophore conjugates, and targeted dosing regimens, clinicians and researchers can pave the way for more effective treatments. Additionally, addressing recurrent UTIs through novel therapeutic regimens, including pulsed antibiotic therapy, holds promise for reducing the burden of these infections while mitigating resistance.

References

-

Saxena, D., Maitra, R., & Bormon, R. (2023). Tackling the outer membrane: facilitating compound entry into Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Nature Reviews. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s44259-023-00016-1

-

University of Utah. (2024). Antimicrobial stewardship to reduce overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in critical access hospitals: measuring a quality improvement intervention. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2024.171

-

Brennand, E. A., & Holroyd-Leduc, J. (2025). Urinary tract infections after menopause. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11790305/

-

Rise of the beta-lactams. (2024). Rise of the beta-lactams: a retrospective, comparative cohort of oral beta-lactam antibiotics as step-down therapy for hospitalized adults with acute pyelonephritis. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2024.70

-

Sgarabotto, D., Andretta, E., Sgarabotto, C., & Karaiskos, I. (2024). Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): A Review and Proposal for Clinicians. Antibiotics, 14(1), 22. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14010022

-

Xilin, L., & Drlica, K. (2024). Examining pharmacoepidemiology of antibiotic use and resistance in first-line antibiotics: a self-controlled case series study of Escherichia coli in small companion animals. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3389/frabi.2024.1321368