Table of Contents

Overview of UTIs and Their Causes

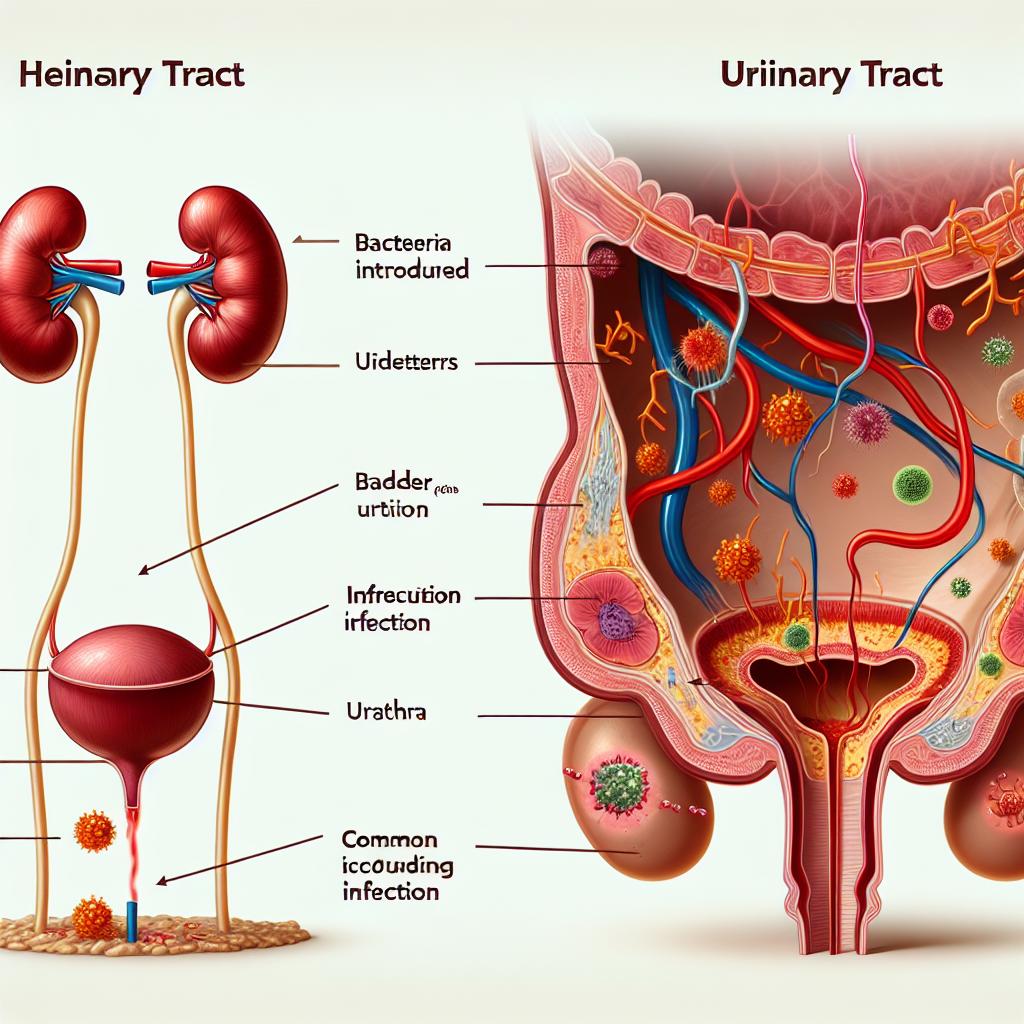

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are prevalent among women, with approximately 50-60% of women experiencing at least one UTI in their lifetime. They occur when bacteria invade the urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, ureters, and kidneys (Smith et al., 2021). The most common pathogen responsible for UTIs is Escherichia coli, accounting for nearly 80-90% of all cases; other pathogens include Klebsiella, Proteus, and Enterococcus species. Factors contributing to the development of UTIs include sexual activity, certain contraceptive methods (like diaphragms), a history of UTIs, and anatomical variations (Abufaraj et al., 2021).

Women are particularly susceptible to UTIs due to anatomical differences, such as a shorter urethra, which facilitates easier bacterial access to the bladder. Other risk factors include hormonal changes, especially during menopause, which can alter the vaginal flora and increase vulnerability to infections (Chen et al., 2020).

How Tampons Affect Vaginal Flora

Tampons are widely used for menstrual hygiene, but their impact on vaginal flora is a subject of debate. The vagina hosts a delicate balance of bacteria, primarily Lactobacillus species, which help maintain an acidic environment that inhibits the growth of pathogenic bacteria. The introduction of tampons, especially if used for extended periods or if they are not changed frequently, can disrupt this balance (Mendes et al., 2017).

Tampons can also absorb not only menstrual blood but also vaginal secretions, potentially leading to a decrease in the protective Lactobacillus population. This disruption can create an environment conducive to the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, increasing the risk of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and UTIs (Jerkovic et al., 2023). The physical presence of the tampon may also irritate the vaginal mucosa, further compromising the local defense mechanisms.

The Link Between Tampon Use and UTIs

While some studies suggest that tampons may contribute to an increased risk of UTIs, findings are not universally accepted. A systematic review examining the association between tampon use and UTI risk noted conflicting evidence. Some studies have reported that the use of tampons did not significantly increase UTI rates, while others highlighted a potential link between prolonged tampon use and urinary infections (Lelie-van der Zande et al., 2021).

The proposed mechanism behind this connection involves the introduction and retention of pathogens. When tampons are left in for too long, they can provide a surface for bacteria to adhere to, facilitating their entry into the urethra. Moreover, if tampons are inserted without adequate hygiene practices, they could introduce bacteria into the vaginal environment, compounding the risk of UTIs (Matarese et al., 2018).

Best Practices for Tampon Use to Prevent UTIs

To minimize the risk of UTIs associated with tampon use, women can adopt the following best practices:

-

Change Tampons Regularly: It is recommended to change tampons every 4 to 8 hours. Avoid leaving tampons in overnight to prevent bacterial growth and maintain vaginal flora balance.

-

Use the Right Absorbency: Choose the absorbency level necessary for your flow. Using a higher absorbency tampon than needed can increase the risk of vaginal irritation and dryness.

-

Practice Good Hygiene: Always wash your hands before and after inserting or removing a tampon. This reduces the risk of introducing bacteria into the vaginal canal.

-

Consider Alternatives: If prone to UTIs, consider using pads, menstrual cups, or period underwear to manage menstrual flow more safely without disrupting the vaginal environment.

-

Stay Hydrated: Drinking plenty of water during menstruation helps dilute urine and flush out the urinary tract, thereby minimizing UTI risk.

-

Consult Healthcare Providers: If UTIs are a recurrent issue, it may be beneficial to discuss alternative menstrual products with a healthcare provider.

Alternatives to Tampons for Managing Menstrual Flow

For women who experience frequent Utis or are concerned about the potential risks associated with tampon use, there are several effective alternatives:

-

Menstrual Cups: These are reusable silicone or rubber cups inserted into the vagina to collect menstrual fluid. They can be worn for up to 12 hours and are less likely to disrupt vaginal flora.

-

Reusable Cloth Pads: Made from cotton or other absorbent materials, these pads can provide comfort and are eco-friendly. They can be washed and reused, which reduces waste.

-

Period Underwear: These garments are designed to absorb menstrual flow and can be worn alone or as a backup to other products.

-

Disposable Pads: For those who prefer a traditional method, disposable pads are easy to use and can be changed frequently to maintain hygiene.

-

Menstrual Discs: Similar to menstrual cups, discs sit higher in the vaginal canal and can be worn during intercourse, making them a versatile option.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Can using tampons cause UTIs?

While there is no conclusive evidence linking tampon use directly to UTIs, improper use, such as leaving them in for too long or poor hygiene, can increase the risk of infections.

How often should I change my tampon?

It is advisable to change tampons every 4 to 8 hours, and they should never be left in for more than 8 hours to minimize health risks.

What are the signs of a UTI?

Common signs of a UTI include a frequent urge to urinate, a burning sensation during urination, cloudy or strong-smelling urine, and pelvic pain.

Are there any alternatives to tampons?

Yes, alternatives include menstrual cups, reusable cloth pads, period underwear, and disposable pads.

What practices can help prevent UTIs while using tampons?

To prevent UTIs while using tampons, maintain good hygiene, change tampons regularly, and consider using products that align with your flow needs.

References

-

Abufaraj, M., Xu, T., Cao, C., Siyam, A., Isleem, U., Massad, A., Soria, F., Shariat, S. F., Sutcliffe, S., & Yang, L. (2021). Prevalence and trends in urinary incontinence among women in the United States, 2005‐2018. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 225(2), 166.e1–166.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.016

-

Chen, H. C., Liu, C. Y., Liao, C. H., & Tsao, L. I. (2020). Self‐perception of symptoms, medical help seeking, and self‐help strategies of women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms, 12, 183–189

-

Jerkovic, I., Bukic, J., Leskur, D., Perisin, A. S., Rusic, D., Bozic, J., Zuvela, T., Vuko, S., Vukovic, J., & Modun, D. (2023). Young women’s attitudes and behaviors in treatment and prevention of UTIs: Are biomedical students at an advantage? Antibiotics, 12, 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071107

-

Lelie‐van der Zande, R., Koster, E. S., Teichert, M., & Bouvy, M. L. (2021). Women’s self‐management skills for prevention and treatment of recurring urinary tract infection. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 75, e14289

-

Matarese, M., Lommi, M., De Marinis, M. G., & Riegel, B. (2018). A systematic review and integration of concept analyses of self‐care and related concepts. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50(3), 296–305

-

Mendes, A., Hoga, L., Goncalves, B., Silva, P., & Pereira, P. (2017). Adult women’s experiences of urinary incontinence: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(5), 1350–1408

-

Smith, A. L., Chen, J., Wyman, J. F., Newman, D. K., Berry, A., Schmitz, K., Stapleton, A. E., Klusaritz, H., Lin, G., Stambakio, H., & Sutcliffe, S. (2021). Survey of lower urinary tract symptoms in United States women using the new lower urinary tract dysfunction research network symptom Index‐29 (LURN‐SI‐29) and a national research registry. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 41(2), 650–661