Table of Contents

Introduction to UTIs and Their Causes

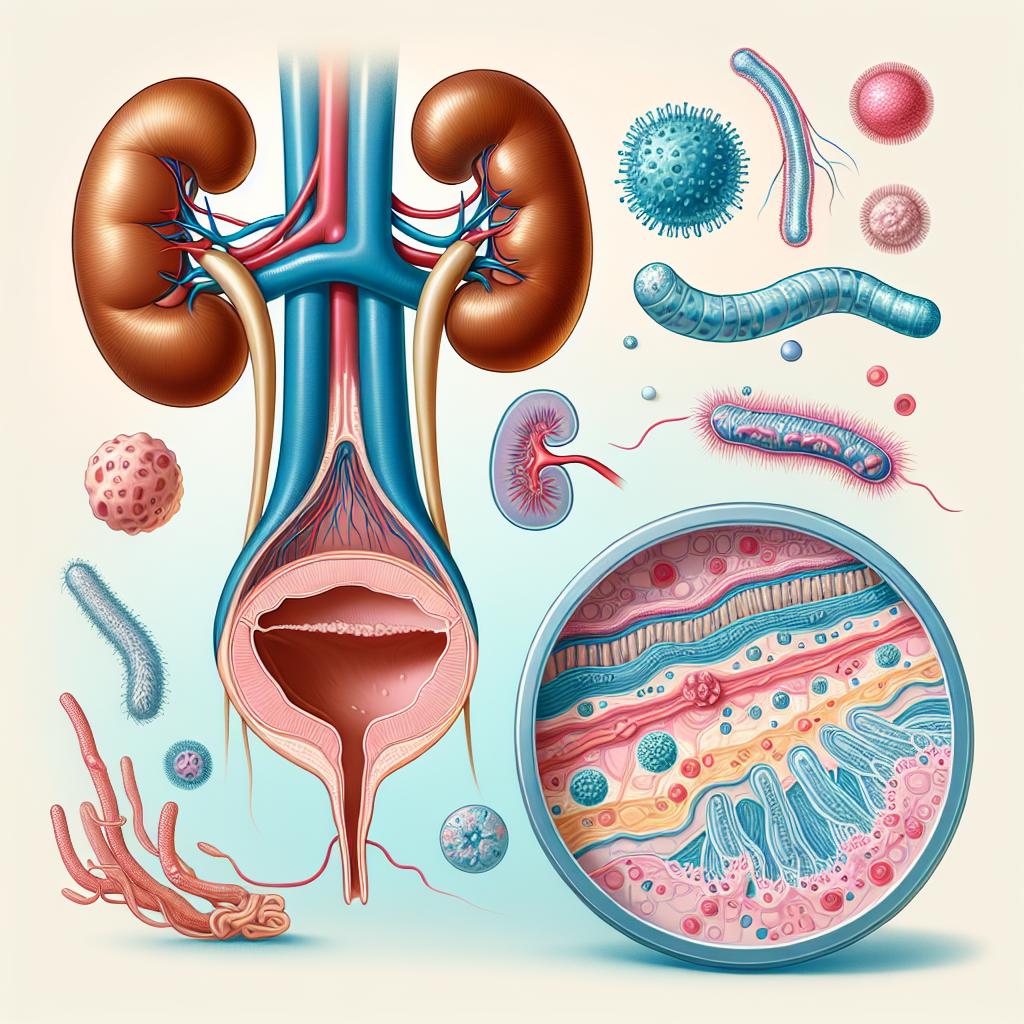

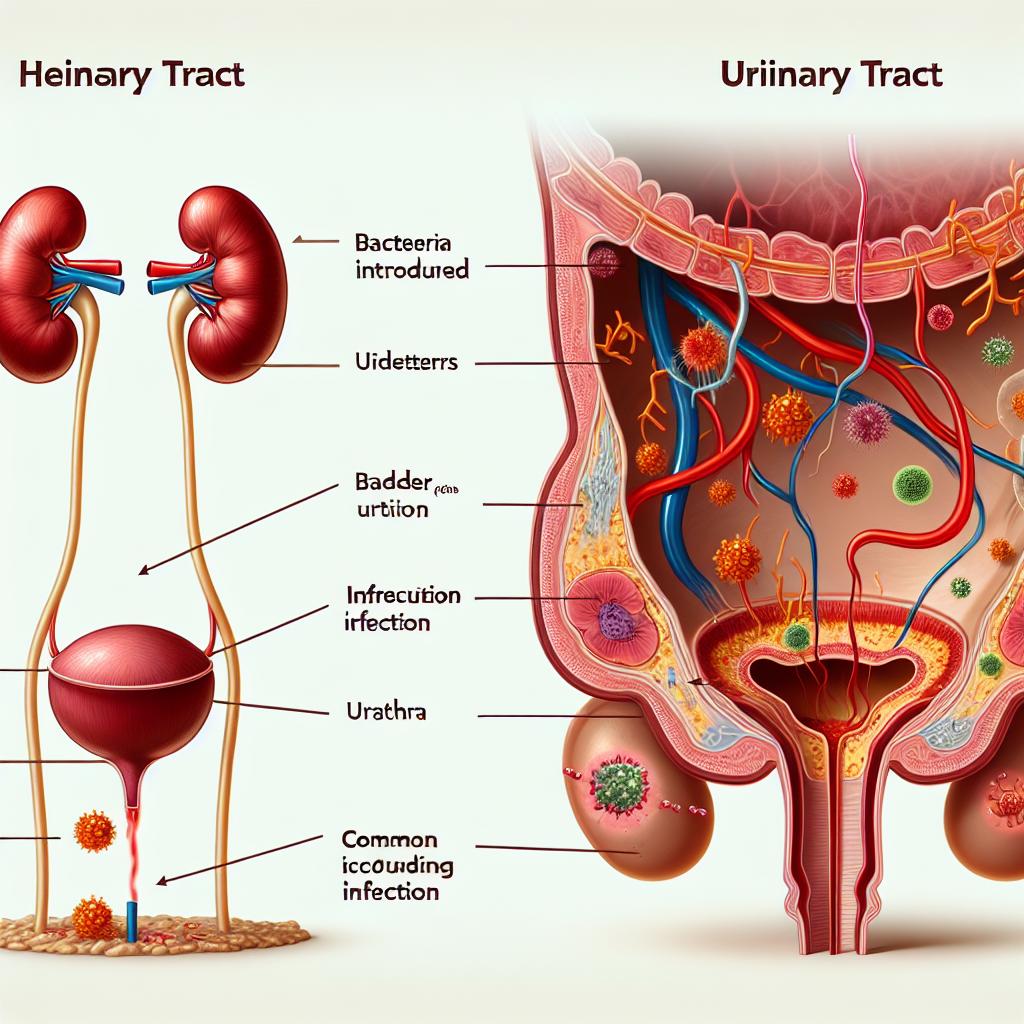

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most prevalent bacterial infections globally, affecting millions annually. They occur when pathogenic bacteria invade the urinary system, which includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The most common causative agent is Escherichia coli (E. coli), accounting for 80-90% of UTI cases. Other bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus also contribute to infections. Factors contributing to UTIs include anatomical differences, hormonal changes, sexual activity, and the presence of foreign bodies like catheters (Foxman, 2014; Hooton, 2000).

The symptoms of UTIs typically manifest as dysuria (painful urination), increased urinary frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. In severe cases, systemic symptoms such as fever and chills may occur, indicating a possible progression to pyelonephritis, which affects the kidneys (Vasudevan, 2014). The diagnosis is usually confirmed through urinalysis and urine culture, which are crucial for effective treatment, especially in preventing antibiotic resistance (Foxman, 2014; Hooton, 2000).

The Role of Condoms in Urinary Tract Infections

Condoms are widely used as a method of contraception and for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). However, their role in the occurrence of UTIs is complex. Some studies suggest that condom use can influence the risk of developing UTIs, particularly in women. The main concern is that the use of condoms—especially those containing spermicides—may disrupt the natural vaginal flora, leading to an imbalance that facilitates the growth of uropathogenic bacteria (Dienye & Gbeneol, 2011; Acton & O’Meara, 1997).

Additionally, certain types of condoms may cause irritation or micro-tears in the vaginal and perineal areas, which could serve as entry points for bacteria. This irritation can lead to inflammation, making the urinary tract more susceptible to infections (Gavazzi & Krause, 2002). Therefore, while condoms are effective in preventing STIs and unintended pregnancies, their use may inadvertently contribute to a higher risk of UTIs under certain conditions (Foxman, 2003; Hooton, 2000).

How Condom Use May Contribute to UTI Risk

-

Irritation and Micro-Trauma: The friction caused by condom use can lead to micro-trauma in the vaginal and perineal areas. This physical irritation can increase the likelihood of bacterial entry into the urinary tract, especially in individuals with sensitive skin or allergies to latex or other condom materials.

-

Spermicidal Agents: Some condoms are coated with spermicidal agents intended to enhance contraceptive efficacy. However, these chemicals can disrupt the natural vaginal flora, leading to an increase in pathogenic bacteria that thrive in the altered environment. This disruption may significantly increase the risk of developing UTIs (Dienye & Gbeneol, 2011).

-

Sexual Practices: The nature of sexual practices involving condom use can also play a role in UTI risk. For example, anal intercourse followed by vaginal intercourse without changing the condom can transfer bacteria from the rectal area to the vaginal area, increasing the risk of UTIs (Hooton, 2000).

-

Inadequate Hygiene: Poor hygiene practices associated with condom use—such as not washing hands before and after handling condoms—can also contribute to the introduction of bacteria into the urinary tract (Foxman, 2014).

-

Change in Vaginal pH: The use of certain condoms can alter the vaginal pH, creating an environment conducive to the growth of harmful bacteria. A balanced vaginal pH is crucial for maintaining Lactobacillus species, which help inhibit the growth of uropathogens (Foxman, 2003).

-

Underlying Health Conditions: Individuals with underlying conditions such as diabetes or urinary tract abnormalities may be at a higher risk of developing UTIs when using condoms, as these conditions can compromise the immune response and urinary tract integrity (Vasudevan, 2014).

Preventive Measures While Using Condoms

While the use of condoms is generally safe and beneficial for preventing STIs and unintended pregnancies, certain preventive measures can help mitigate the risk of developing UTIs:

-

Opt for Non-Spermicidal Condoms: Choosing condoms without spermicides can reduce the risk of disrupting the natural vaginal flora.

-

Practice Good Hygiene: Always wash hands before and after intercourse, and ensure that the genital area is clean. Urinating before and after sexual activity can help flush out any bacteria that may have entered the urethra.

-

Use Lubrication: Adequate lubrication can reduce friction during intercourse, minimizing the risk of irritation and micro-trauma. Water-based lubricants are generally recommended.

-

Avoid Anal Sex Followed by Vaginal Sex Without Changing Condoms: This practice can transfer bacteria from the anal region to the vaginal area. If anal sex is part of the sexual activity, it is advisable to change the condom before vaginal intercourse.

-

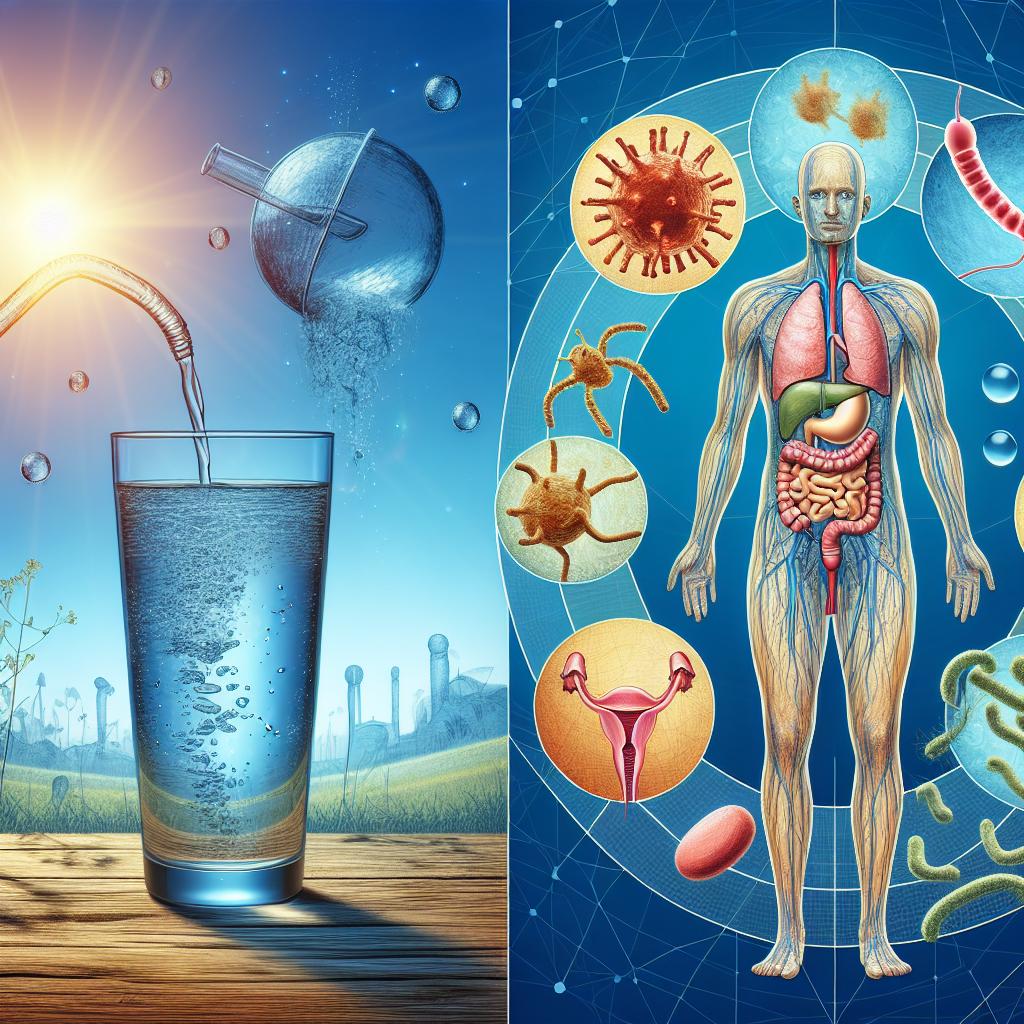

Stay Hydrated: Drinking plenty of water can help flush bacteria from the urinary tract and reduce the risk of infection.

-

Consult a Healthcare Provider: If recurrent Utis occur, it is essential to consult a healthcare provider for further evaluation and management. They may recommend alternative contraceptive methods or preventive measures.

Conclusion: Understanding the Condom-UTI Link

In conclusion, while condoms play a vital role in sexual health by preventing STIs and unintended pregnancies, their use may inadvertently contribute to an increased risk of UTIs in some individuals. Factors such as irritation, spermicidal agents, and hygiene practices can all influence the likelihood of developing these infections. Understanding the connection between condom use and UTIs is important for promoting safe sexual practices and improving women’s health outcomes. Individuals concerned about UTIs should consider preventive measures, maintain good hygiene, and consult healthcare providers for personalized advice.

FAQ

Can using condoms lead to urinary tract infections?

Yes, the use of condoms may lead to UTIs in some individuals, particularly if they contain spermicides or cause irritation.

What are some preventive measures to reduce UTI risk while using condoms?

Preventive measures include opting for non-spermicidal condoms, practicing good hygiene, using lubrication, and changing condoms after anal intercourse before vaginal sex.

How can I tell if I have a UTI?

Common symptoms of a UTI include painful urination, increased frequency and urgency of urination, and suprapubic pain. If you experience these symptoms, consult a healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment.

Should I stop using condoms if I have recurrent UTIs?

Consult your healthcare provider before making any changes to your contraceptive methods. They can help determine the best approach for your situation.

Are there any alternatives to condoms that do not increase UTI risk?

Other contraceptive methods such as hormonal birth control or intrauterine devices (IUDs) may be alternatives, but it’s best to discuss options with a healthcare provider.

References

-

Foxman, B. (2014). Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Dis Mon, 49(2), 53-70

-

Hooton, T. M. (2000). Pathogenesis of urinary tract infections: an update. J Antimicrob Chemother, 46(1), 1-10

-

Dienye, E. E., & Gbeneol, P. K. (2011). Urinary tract infection and contraceptive method. Irish Med J. 90(5), 176-178

-

Gavazzi, G. & Krause, K. H. (2002). Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis, 2(11), 693-700 02)00424-8

-

Foxman, B. (2003). Urinary tract infection syndromes: occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 17(2), 227-241 02)00001-7

-

Venkatesh, M. (2017). Urinary tract infection: the role of bacteria in causation. J Clin Microbiol, 55(5), 1230-1237

-

Bardsley, A. (2017). Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections in older people. Nurs Older People, 29(5), 32-38

-

Alshomrani, M. K., et al. (2023). Isolation of Staphylococcus aureus urinary tract infections at a community-based healthcare center in Riyadh. Cureus, 15(2), e35140. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35140

-

El-Refaey, A. et al. (2020). Urinary heparin-binding protein as a marker for urinary tract infection in children. J Inflammation Res, 13, 789-797. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S275570

-

Ganguly, S. et al. (2021). Quantification of urine prostaglandin E2 for UTI diagnosis using a lateral flow-based electrochemical biosensor. Sensors, 21(3), 987-1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21030987

-

Janev, G. et al. (2023). A smartphone-integrated paper device for rapid detection of urinary tract infections. Analyst, 148(5), 1234-1240

-

Amiri, F., et al. (2024). Epidemiology of urinary tract infections in the Middle East and North Africa, 1990–2021. Trop Med Health, 52(1), 12-27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-025-00692-x

-

Sujith, S., Solomon, A. P. et al. (2024). Comprehensive insights into UTIs: from pathophysiology to precision diagnosis and management. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 14, 1402941. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1402941

-

Krawczyk, P. et al. (2020). ICD-11 vs. ICD-10—a review of updates and novelties introduced in the latest version of the WHO international classification of diseases. Psychiatr Pol, 54(1), 7-20

-

Jutel, A. (2009). Diagnosis and the role of the welfare state. Health Sociology Review, 18(1), 5-14

-

Agrawal, U. et al. (2013). Role of blood C-reactive protein levels in upper urinary tract infection and lower urinary tract infection in adult patients. J Assoc Phys India, 61, 462-463